Lula Witzescher wrote the following text for the programme of Berlin Open 2016. Since it has caused quite some controversy and discussion already at Berlin Open, we are now presenting the text in English here (translation: Tina Ottenheym). May a broad, varied and constructive discussion begin.

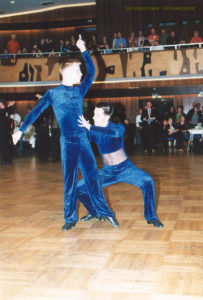

Warm-up / Ballroom. At first glance I am not sure whether I really am at an Equality tournament: couples in dress / suit combinations are dancing just like “normal” woman-man-couples. Only at a second glance I spot one couple sporting an outfit which is not clearly marked for a certain gender. The men show an entirely different picture: almost every couple dances in suits. To me, it seems as if the women interpret the term “equality” as “the equivalent to mixed-gender dancing”, while the men follow the interpretation of “similarity”. And here I was thinking “equality” meant the equality between the sexes!

And as usual, I ask myself: why are so few dancers using this opportunity to move outside traditional standards?

At my first tournament, I was enchanted by the variety: the diversity of the couples and their clothes, the large age-span, the various interpretations of leader and follower roles. I saw indefinite possibilities that were entirely independent of sex or gender, but that rather were about the expression of different personalities.

The picture, however, changed with the years. I am sure there are some women among the dancers who fulfil their secret wish to float across the dance floor like a princess in a bouffant dress. Back in the day, when I exchanged my XL-shirt for a combination of tight waistcoat and push-up-bra, it felt as if I had discovered a new personality within me, and it felt incredibly wonderful.

Images and concepts help us find our way through life by automatically making assessments. However, they can often be misleading when they quite literally are out of the ordinary.

Back then, I wished to find a place within same-sex dancing where I could be out of the ordinary without having to explain myself all the time. For example, why I, a woman measuring two metres, also wanted to follow instead of lead. But sadly, I experienced being forced to lead at a trial training, despite my protests. It was obvious that I was supposed to lead, with my height. Really? Why exactly? We could not win the argument, and consequently never went back there. We were not the kind of people to do something „because it has always been done that way“, but instead wanted to bring our own imaginations to the dance floor. It was not easy to find people who supported us. Some objections may have had their justification: it is harder to lead when I only see my partner’s breasts in front of me. But harder does not mean impossible. For me, it was always about asking questions and finding answers that suit me and my purposes. I, for one, would never wear a mask-like make-up, for I cannot associate the generally accepted picture of “expressive” with it, however hard I might try.

Same-sex dancing is still struggling for acceptance. Collaborating with the German Dance Association (DTV) has meant that the definition of same sex dancing is directly related to that of the mainstream. This seems to have manifested in same sex dancers emulating the mainstream to fit expectations and we see this in how many are presenting themselves on the floor.

But another question is occupying my mind: why do women follow traditional gender roles, while the men do not?

A natural explanation would be the effect of everyday gender discrimination. No man voluntarily makes himself a woman, that is to say: weak. In the course of the past years, there were some few men who were a bit more adventurous and wore high heels to their suits or put a small chiffon flag on their clothing. However, it was clear that there always has been an unspoken boundary. Sporting a dress or a skirt would have made any man a laughingstock at best.

For me, the switch between leader- and follower role is an indispensable element and I am surprised over how few couples are using this element. One possible reason might be that switching roles requires more effort in order to get an equally good result compared to not switching. Another reason might be that the judges use the same criteria in both same-sex and mixed-sex dancing, making the role switch a disadvantage.

Let us take the point of „couple harmony“ as an example. What do we define as being in harmony? We are influenced by the general picture of the man being taller than the woman. This was the origin of the classical dancing aesthetic which is generally accepted as being harmonic. This is also the picture we base our judgement of same-sex dancing couples on: the leader should be taller than the follower, and both should use the classical aesthetic. But does it have to be this way? Perhaps the question ought to be: who defines “appearance in harmony“? And who questions the definition?

As long as the criteria – consciously or unconsciously – are based on traditional images, it is of course hard to be successful in digression from the image. But for some of us this is about more than winning. For some of us, it is fortunately still a free space which we must use and fight for in the future. For in the end, it is the couples who decide how much heteronormativity (and female discrimination) they want to present on the dance floor.

Author Lula Witzescher fights for all forms of Equality online. twitter.com/LulaWitzescher